|

| Actual conversation of this picture: Me: But whyyyyy? Them: Okay. |

Why do people speak in honorific language?

It is Korean culture.

But why is it Korean culture?

Everyone does this.

But why do they do this?

We were taught by our families?

But why do people teach their children to speak with honor, politely, to people older than them?

...

Keunyang. “It just is.”

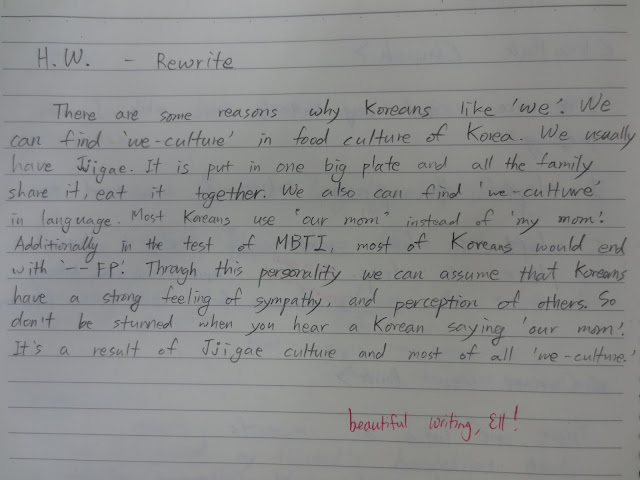

You can feel the frustration rising from both me and my students when this conversation happens. I feel like a four year old, asking the same question over and over again why? why? why? My students, on the other hand, can’t answer and even though they think I’ve contracted some kind of whydisease, never ask my question back at me. “Why, teacher?” never happens.

You can feel the frustration rising from both me and my students when this conversation happens. I feel like a four year old, asking the same question over and over again why? why? why? My students, on the other hand, can’t answer and even though they think I’ve contracted some kind of whydisease, never ask my question back at me. “Why, teacher?” never happens.

But my whys never stop. The clever kids come up with, “It is traditional Korean culture” in response to my whys, but eventually, as demonstrated above, we always come back to it: keunyang.

Nothing, I lecture my students with an eyeroll, just is. We don’t even have this concept in English because there are reasons for things, but if we did, anyone caught using keunyang would be laughed out of the room. It’s not as though Koreans don’t understand the concept of “because;” on the contrary, they use that expression with ease. The glitch in communication comes when a westerner (me) expects individual thought, individual becauses, and this is where we turn to the dark side of “we Culture.”

If I asked a classroom full of American college students to list “things to do in an elevator,” the whiteboard would be plastered with every student’s efforts to come up with the most novel idea, the clever idea, the one that would set them apart. They would have attacked the question from all sides, imagining the different scenarios in which one was in an elevator. Who with? When? Where? Why? How? to come up with the answer to the what.

Nothing of the sort happened when I gave this assignment to my Korean students as a race. For them it wasn’t a race to be clever; it was a race to delineate all the proper answers they had each been taught before--a race, I might argue, to be the most ordinary. And in doing so they found every single boring answer possible. Some, I think, were so obvious that Americans would have missed them such as “go up” or “breath.”

Korea is an entire nation of unquestioning obedience, accepting cliches and common truths from authority figures as the final arbiter of right action. It all makes an American slightly sick, quite frankly. We learned to criticize our culture from kindergarten, to analyze leaders for their faults and virtues, to evaluate teachers on their technique, to question why why why why why until our parents probably wanted to shut us all in the upstairs closet until we passed that phase, except that curiosity is a good thing that leads to knowledge and then to wisdom.

Korea is an entire nation of unquestioning obedience, accepting cliches and common truths from authority figures as the final arbiter of right action. It all makes an American slightly sick, quite frankly. We learned to criticize our culture from kindergarten, to analyze leaders for their faults and virtues, to evaluate teachers on their technique, to question why why why why why until our parents probably wanted to shut us all in the upstairs closet until we passed that phase, except that curiosity is a good thing that leads to knowledge and then to wisdom.

However, that idea - curiosity=>knowledge=>wisdom - is not necessarily true. It is American. Or, more accurately, a Western thought originating from our Enlightenment period.

I’m not saying I don’t agree with it, nor that it’s useful in a wide variety of circumstances. Questioning authority and individual curiosity is, after all, what gave us the Reformation, rock and roll, and electricity, and I like all of those things (Luther is baller). But the “we culture” and keunyang” brought Korea one of the most impressive economic turnarounds the world has ever seen. Korea perches proudly in the middle of unfriendly giants China and Japan and crazy Kim Jong Un, strong and united the way America never has been or (perceivably) will be.

Moreover, and more applicable, keunyang is how Koreans make it through. Through what, you ask?

Don’t.

Stop asking questions and let things keunyang.

That is my goal for my next few weeks, finishing up my time here in Korea: keunyang-ing it.

Ask the question, search the available database of authoritative answers and, if you come up empty, keunyang.

Why can’t my students understand my directions? Keunyang.

Why do they cut up their faces to look pretty? Keunyang.

Why don’t they read books? Keunyang.

Why don’t they ask questions? Keunyang.

Why did that old lady shove me into the gutter on her way up the bus steps? Keunyang. |

| Why do all my students dress better than me and have nicer smartphones? Keunyang! |